When Michelle Gadsden-Williams first suffered unexplained fever, body aches and chills, she was sure she had the flu. Soon she developed chronic fatigue, swollen ankles and stiff, painful joints. Next, her walks up and down a flight of steps brought on chest pains. In addition, she lost an excessive amount of hair and became ultra-sensitive to the sun.

“I went to the doctor, and he actually diagnosed me as having the flu,” she recalls. “So I took my medication and went about my business.”

But after about a month, Gadsden-Williams’s symptoms returned. Then the frequency of these signs escalated. “It was happening once a month, and then it started progressing in a very rapid fashion,” she says.

In 2005, Gadsden-Williams, then a pharmaceutical industry executive, went to see a specialist. She and her husband were considering having a family, but she was unable to get pregnant. After the specialist and a reproductive doctor conducted comprehensive tests, they both noticed that her inflammation levels were high. One doctor asked her if she’d ever suffered from Lyme disease. Maybe this was a plausible possibility, Gadsden-Williams thought. She did live in an area where a lot of deer roamed in her backyard. Her doctor prescribed three days of antibiotic treatment. But about two months later, her symptoms returned.

Puzzled and uneasy, Gadsden-Williams returned to see her primary care physician. He thought her illness might be something autoimmune, so he ordered more aggressive testing. Then she went to see a rheumatologist who specialized in lupus and learned she had systemic lupus erythematosus, or SLE, one form of the disease.

Gadsden-Williams says at that time she didn’t react to the diagnosis because now her illness had a name. In addition, she also had a decision to make. “I was just about to relocate to Switzerland to assume a new position,” she says.

As she thought about her iffy health status, questions ran through Gadsden-Williams’s mind. Should she stay home, or should she go abroad? And if she went overseas, what would she do if she became ill?

Eventually, she decided to go to Switzerland and take the promotion at the company where she’d worked for 10 years. But Gadsden-Williams stayed mum about having lupus. She was afraid. “I had just assumed the position of my dreams, and I didn’t want to be labeled as fragile, or have people think I was sick and wouldn’t be able to do my job effectively,” she says. “So at that particular time, I decided to keep that information to myself. When my legs would swell, I wore pantsuits. I did everything to hide the fact that I was battling a chronic illness.”

Finally, Gadsden-Williams shared her situation with her co-workers when it became clear they knew something was wrong. “I decided to just speak the truth,” she says.

When she told her boss, she was surprised by his reaction. “He said, ‘I’m disappointed in the fact you didn’t feel that you could trust me with that information and you have a lot of support here. People care about you and we want to support you in any way we can,’” she says. “In hindsight, I think I would have at least told those individuals who really needed to know my situation.”

According to the S.L.E. Lupus Foundation, lupus affects 1.5 million Americans and millions more worldwide. The autoimmune disease most often strikes women, and African-American, Asian-American, Native American and Latina women are more likely than Caucasian women to develop the illness. What’s more, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status also play a role in the health outcomes for people living with lupus. Says Edward H. Yellin, PhD, author of a paper on lupus and health disparities published in The Rheumatologist, “persons with SLE of lower socioeconomic status have poorer outcomes of disease and higher death rates.”

In 2009, Yolanda Randolph, a culinary school graduate living in Brooklyn, New York, learned she’d developed SLE. “Lots of sores appeared on my left thigh that just came out of nowhere,” she says of the symptoms that began in 2001. “That happened several times, and doctors didn’t know what it was.”

After Randolph got a tetanus shot to start a job as a cook at a local family services agency, her health worsened, so she went to the doctor. That’s when she tested positive for lupus. “I knew something was wrong because these sores just kept coming,” she says. “But lupus was the last thing I expected it to be.”

Randolph knew about lupus; the illness runs in her family. “I had a cousin who died of lupus; she was 26,” Randolph says. “And one of my aunts had it, but she had very little difficulties from the lupus. Other things kicked in, and she had problems with her organs and then cancer.”

Besides the genetic risk factor, no one knows exactly what causes the disease. “Many (but not all) scientists believe that lupus develops in response to a combination of factors both inside and outside the body, including hormones, genetics and environment,” says the Lupus Foundation of America.

But for Randolph, how she developed lupus was the least of her concerns. She was more worried about how she’d be able to afford treatment. She had no health insurance. When she suffered lupus flares—a period of time when symptoms occur—she’d seek care at the emergency room. Then, after getting signed up for Medicaid, sometimes her coverage would lapse. “The doctors in the emergency room would give me medication to hold me for seven days until I could get to a doctor,” she says. “But, in most cases, you don’t get to see a doctor without insurance. I would experience a domino effect, get sick, go back to the emergency room and let the doctors give me more medication until I could get back on Medicaid.”

|

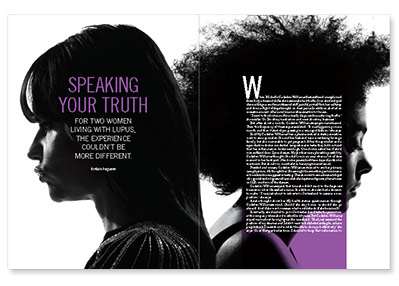

| Michelle Gadsen-Williams (left) and Yolanda Randolph had extremely different responses when they disclosed they had lupus to employers |

Randolph’s experience mirrors the findings of studies that show nonwhite people living with lupus who are of a lower socioeconomic status have higher incidences of the disease, more severe forms of the illness and higher death rates from lupus. Findings also show that race, socioeconomic status and closely associated factors—such as decreased access to quality health care, reduced comprehension of disease and the medical system, increased competing home and work demands, and a reduction in self-confidence and social support—were closely connected and predicted SLE activity, organ damage and the ability of lupus sufferers to function.

Randolph understands lupus very well, and she is still highly functional. But she doesn’t know why getting health care for her chronic condition is so difficult. “It’s so hard to get into an insurance program. It doesn’t matter whether your illness is chronic or minor; everybody has criteria that you don’t meet,” she says. “The system doesn’t seem to help people who really have a chronic illness and need medication and hospital visits often.”

She’s also facing difficulty securing a safe place to live and finding and holding onto a job. Shortly after being hired by a major food retailer, she became ill and wound up in the hospital. “Two days after I gave them my doctor’s notes, I was fired,” Randolph says.

Another hired-then-fired episode saw Randolph lose her job at a popular family restaurant franchise. By then, she had enrolled in a clinical trial and was receiving weekly infusions of a new lupus drug. Says Randolph, “Jobs don’t work out all that well because once employers find out you’re sick, that’s it.”

Even managers at a federally funded program that works with companies who hire employees with disabilities cautioned her not to tell employers about her illness, Randolph says. “I’m just trying to find employment with an employer who understands that I have an illness, but I am employable.”

Gadsden-Williams regularly speaks to women with lupus about how to disclose they have the disease to employers. “You must have that courageous conversation in a way that’s going to be most meaningful for you because you’re revealing your truth to a perfect stranger,” she says. “I coach them in terms of how to have that constructive conversation because they’re asking for what they need in order to be successful and they’re asking for people to be patient.”

But she also concedes that companies should be more sensitized to their employees’ health issues by having “internal conversations about how to lead and engage with people in general.” And there needs to be a support system in place, especially for employees living with chronic illnesses. Says Gadsden-Williams, some companies, such as Credit Suisse Bank, where she’s the global head of diversity and inclusion, offer their employees wellness programs and institutionalized support systems. But she understands that not all companies provide these benefits.

“We’re starting to have more of these conversations, but it’s still a challenge,” she says. “People don’t like to talk about health in the workplace.”

Comments

Comments